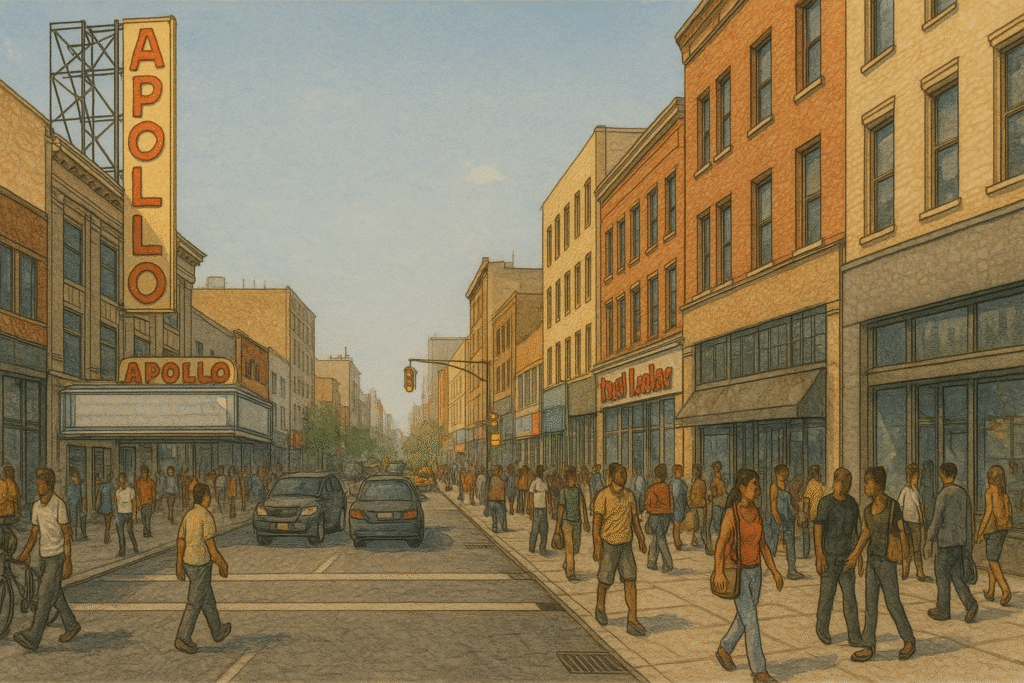

Enjoying New York City to the fullest means understanding its rhythms, cultures, and contrasts — and that means seeing more than Manhattan alone. If you’re visiting for more than a day or two, don’t stop at Times Square and SoHo. Even native New Yorkers discover something new when they explore a different neighborhood.

If this is your first time visiting, you’re probably overestimating how much sightseeing you’ll accomplish. Walking, taking the subway, pausing for food consumes time, energy, and attention. Be strategic with your time, especially if it’s limited to a few days.

Looking to check off major landmarks in one shot? See our 1-Day Photo Mission Guide for hitting NYC’s iconic spots in record time.

If you’re drawn to the other New York, the one that unfolds through side streets, spontaneous moments, and small public rituals, congratulations, you’re doing it the New Yorker’s way.

Jump to Anywhere in this article.

Planning a satisfying day in NYC isn’t about cramming everything into your day. It’s about budgeting your time wisely and being deliberate about what you do and where you go. The key is to design your day with a rhythm:

One or two main activities

A few solid food stops

And intentional downtime

Timing matters more than you think. For example, if you try to get lunch between 11:00 AM and 1:00 PM in Midtown, you’ll run into the midday rush — when workers spill out into the streets and food lines become crowded. You can plan around that.

This guide will show you how to structure your NYC day. With smart pacing and borough-spanning ideas, you’ll enjoy more of what the city actually offers besides the typical tourist routes.

Exercise

In Manhattan

Manhattan offers an abundance of ways to engage your body in motion, especially if you’re looking for experiences that are free, open to the public, and local. The Hudson River waterfront is home to several dynamic outdoor activity spaces that are both accessible and scenic. At Pier 26, the Downtown Boathouse provides free kayaking during the warmer months. It’s a simple but energizing experience — 20 minutes of paddling with all equipment provided and volunteers available to guide you. Just north, Pier 62 features one of the best-designed skateparks in the city: a concrete playground with bowls, rails, and sweeping river views, open to skaters of all levels.

Further uptown, Shape Up NYC classes are offered in select Manhattan parks and recreation centers — including strength training, dance cardio, and yoga. These are open-level, free of charge, and usually hosted on open lawns or basketball courts. At Riverside Park near 100th Street, you’ll also find one of the only outdoor public climbing walls in the borough, staffed during open hours and suitable for beginners. And throughout the borough, the Hudson River Greenway offers a reliable route for cycling, jogging, or walking — with breezes, skyline views, and minimal traffic interruption.

Each of these active spaces pairs naturally with nearby downtime options. After kayaking or skating downtown, Teardrop Park offers a compact, quiet environment tucked into Battery Park City. With terraced stone seating and plenty of shade, it’s ideal for a reflective pause. The wide green at Pier 45, just a short walk from both Pier 26 and 62, offers space to lie down, snack, or decompress beside the river. If you’re uptown after a workout or a climb in Riverside Park, you’ll find quiet benches nearby surrounded by flowers and elevated views. These parks and riverfront lawns aren’t just places to rest — they’re part of the city’s rhythm, offering softness and calm right after exertion.

In Manhattan, physical movement and restorative quiet are often just blocks apart. You don’t need a gym to break a sweat, and you don’t need to go far to let the experience settle. Planning a day with both in mind will not only help you stay energized — it’ll help you move through the city with intention. Read our free activities guide for classes and workshops in Manhattan and then unwind at one of Manhattan’s parks closest to your activity.

In Brooklyn

Brooklyn’s energy is grounded in the neighborhoods — where community gardens double as workout spaces, and local gyms spill into playgrounds and parks. Movement here often happens close to home: through classes hosted by neighborhood rec centers, or informal groups gathering in open fields. Shape Up NYC offers free fitness programming in several Brooklyn parks, including strength and cardio sessions in Fort Greene and Crown Heights. These classes often take place in the morning or early evening, and are attended by locals of all ages. Just being there puts you into the everyday rhythm of the borough.

In Gowanus and Bed-Stuy, independent boxing gyms and martial arts studios run low-cost group sessions that welcome drop-ins. The energy is high, the spaces raw and practical, and the culture is often shaped by regulars — meaning you’ll get a real sense of the neighborhood even if you’re only there for an hour. In Prospect Park, movement is as open-ended as you want it to be: group runs, yoga meetups, casual dance practice, or just a fast-paced walk through the Long Meadow. The park’s scale and centrality make it one of the city’s most versatile locations for self-guided activity.

After exertion, you don’t need to travel far to find quiet. If you’re working out in Fort Greene, the park itself offers stone steps, shaded benches, and tree-lined paths for cooldowns. Near Gowanus, Thomas Greene Playground offers modest green space to sit, stretch, or drink water. And Prospect Park is its own reward: the north woods, Nethermead, and tucked-away lawns all offer silence just a few minutes from open fields. When planning your rhythm in Brooklyn, the movement and the rest often happen within blocks of each other — a reflection of the borough’s density, softness, and local pace.

In Queens

In Queens, physical activity often unfolds in neighborhood parks and cultural hubs — places where the diversity of the borough is not just visible but felt in how people gather and move. Jackson Heights’ Travers Park is one of the most active community spaces in the borough. On any given day, you’ll find tai chi circles, seniors stretching in the early morning, or local fitness instructors leading small-group workouts in multiple languages. These are informal and inclusive — you don’t need to sign up.

Farther east, Astoria Park stretches along the East River with expansive lawns and fitness areas under the Triborough Bridge. It’s a go-to spot for runners, cyclists, and group workouts, and its wide open space makes it feel less like a city park and more like a social field. In Jamaica, the Jamaica Center for Arts & Learning occasionally offers public movement or wellness workshops as part of its cultural programming. The focus here isn’t intensity — it’s presence. Movement in Queens is local, unhurried, and community-powered.

Downtime is never far away. From Travers Park, the calm is built in — just find a shaded bench or sit along the edge of the small plaza where families gather. In Astoria, you can cool off with a slow river walk just below the main lawn, or rest under the trees overlooking the water. Gantry Plaza State Park, while technically on the Long Island City waterfront, is a short ride away and offers skyline views with wooden loungers, boardwalk paths, and grassy stretches that feel made for pause. In Queens, motion and recovery often share the same space, inviting you to shift gears without leaving the block.

In The Bronx

The borough’s fitness culture is shaped by space: wide-open parks, riverside greenways, and elevated viewpoints.

Capoeira and group fitness sessions are frequently held in community spaces like Soundview Park or the fields near Fordham, especially during warmer months. These gatherings are energetic but accessible, with no formal entry points — just people showing up, stretching, and joining the flow. Shape Up NYC runs classes in Claremont Park and St. Mary’s Park, both central and deeply rooted in local use. And the Bronx River Greenway offers one of the most restorative and dynamic walking or running routes in the city — especially in the stretches near Concrete Plant Park or Hunts Point Riverside.

Downtime in the Bronx tends to lean toward the expansive and natural. Soundview Park, where many fitness activities happen, doubles as a decompression zone: wide salt marsh paths, benches along the water, and space to lie in the grass or just watch the light change. Nearby, Concrete Plant Park provides a quieter, more architectural pause — a small, art-infused space just off the Greenway that offers shade and solitude. For something immersive, the New York Botanical Garden (paid admission) is not only one of the most beautiful environments in the city but also one of the quietest. Its wooded paths and hidden benches offer recovery in both body and attention.

In the Bronx, activities like classes and workshops are never far from nearby parks and often exist in the same place. You don’t have to travel far between motion and stillness — the landscape has already been shaped to hold both. The rhythm here is natural, unapologetic, and built to carry you without hurry.

In Staten Island

Staten Island’s physicality is shaped by space. Unlike the other boroughs, where movement often weaves through dense streets or small parks, Staten Island offers vastness — trails, hills, open coastlines, and forested zones where the activity isn’t just allowed, it’s amplified by the landscape. Movement here feels quieter, slower, and more rooted in the terrain.

Hiking and trail running are especially rewarding in the Staten Island Greenbelt, a vast, interconnected stretch of woods, wetlands, and unpaved paths. It’s one of the few places in the city where you can truly disappear into a forest. Willowbrook Park, which touches the Greenbelt’s western edge, is another launch point — ideal for light jogging, group nature walks, or quiet solo movement. On the coast, seasonal kayaking programs run by organizations like Kayak Staten Island offer beginner-friendly paddling experiences just off the southern shoreline. These events are relaxed and well-supported, with volunteers and gear provided, and are usually clustered around weekends in warmer months.

Once you’ve exerted yourself, the opportunities to slow down are immediate and generous. Willowbrook Park doubles as a downtime destination, with shaded benches, quiet picnic zones, and long, gently sloping lawns that feel far from the city. For views and solitude, Fort Wadsworth offers a dramatic coastal overlook of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge and New York Harbor — a space where you can sit quietly for an hour and feel the scale of the city shift. Closer to the ferry terminal, the promenade along the waterfront provides a breezy, well-paved stretch with benches, views, and room to breathe — an ideal cool-down loop before heading back into the fray.

In Staten Island, motion is immersive. It happens in the open — on forest paths, quiet water, or under a changing sky. The rhythm here is less about what the body does and more about what the landscape invites. And in most cases, the stillness comes built in.

Creative Engagement

In Manhattan

New York’s creative life doesn’t only exist in galleries or behind closed doors. In Manhattan, you’ll find countless opportunities to join in — whether by making art in public spaces, participating in workshops, or simply engaging in spontaneous performance-based activities that bring strangers together. These experiences are often unstructured, low-cost, and open to anyone who’s curious enough to show up.

Throughout the year, NYC Parks sponsors public art workshops and participatory installations across the city. In Manhattan, these often appear in downtown plazas or community gardens — events where passersby can paint, sculpt, or contribute to collaborative pieces in real time. In Midtown and the West Village, improv theaters like the Magnet and The PIT offer casual drop-in classes and open mics, which provide a low-pressure environment for trying something new or flexing your creative muscles. These spaces aren’t exclusive — they thrive on participation and experimentation, often welcoming total beginners alongside regulars. In select locations, the city also partners with local organizations to host seasonal arts programming in parks and libraries, including community mural painting, bookmaking, and zine-crafting events.

Once you’ve created or performed, it’s worth transitioning to a space that lets the energy taper off without disappearing. Greenacre Park, a quiet Midtown hideaway framed by ivy-covered walls and a waterfall, is just a short walk from many of these creative venues. If you’re near the West Village or downtown, Jefferson Market Garden offers a gated patch of flowers and benches beneath the clocktower — a spot that feels more like a tucked-away courtyard than a city park. Farther south, Bogardus Plaza in Tribeca offers open seating in a neighborhood known for its design-forward storefronts and coffee options. These spots are ideal for reviewing what you just made, having a reflective conversation, or simply letting the buzz of a creative experience fade gently into stillness.

Creative engagement in Manhattan is often informal and surprisingly accessible. When paired with a calming nearby space, even a short burst of expression can add a layer of connection to your day — with yourself, with others, and with the city around you.

In Brooklyn

Brooklyn’s creative energy is neighborhood-based and grounded in access — art that isn’t sealed behind a ticketed door but spread across community centers, converted warehouses, sidewalk walls, and public libraries. Here, creative engagement tends to blur the lines between audience and artist. You don’t need credentials to contribute — you just need to show up.

In Gowanus, studios and ceramics spaces offer drop-in sessions where beginners can work with clay or paint in open formats, often by donation or on a sliding scale. These are intimate, process-focused environments tucked inside converted industrial buildings. In Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights, community centers and independent cultural groups host free or low-cost creative workshops — zines, drawing, journaling, or collaborative mural painting. The vibe is often informal and responsive: someone brings supplies, a few people show up, and something takes shape over the course of an hour. This is not a gallery scene — it’s art as a neighborhood ritual.

After creative output, Brooklyn offers no shortage of places to retreat. If you’re working in Gowanus, Prospect Park is just a short ride or moderate walk away, offering both wooded solitude and open meadows. The shaded benches near the Vale of Cashmere or along the Parkside Avenue edge are especially well-suited for processing and quiet sketching. In Fort Greene or Bed-Stuy, Fulton Park and Herbert Von King Park provide smaller but peaceful spaces to cool down after a creative session — shaded, used, but rarely loud. The Brooklyn Heights Promenade, though farther away, is worth the extra travel if you want space to decompress with a skyline and breeze.

Creative expression in Brooklyn is something you participate in, not consume. And when paired with a reflective green space nearby, it becomes part of your own rhythm — not just a checkmark, but a shift in how you move through the day.

In Queens

In Queens, creative activity is closely tied to language, heritage, and public gathering. Artistic expression often happens in shared civic or cultural spaces — libraries, plazas, and neighborhood arts centers — and reflects the deep mix of backgrounds that shape the borough. It’s not performance for spectacle, but for community, identity, and presence.

The Jamaica Center for Arts & Learning is one of the borough’s anchors for participatory creativity. Its public-facing workshops range from mural painting to movement and drawing, and they’re often structured to welcome people with no formal experience. On the other side of Queens, smaller programs connected to local libraries or community centers — particularly in neighborhoods like Jackson Heights or Corona — host seasonal workshops for zine-making, journaling, and hands-on book arts. These sessions are typically small, often run by local artists, and emphasize personal storytelling over technique. There’s also an ephemeral quality to many of these events — they may not happen on a schedule, but they’re visible, public, and easy to join when they do.

After an hour or two of creative work, Queens offers pockets of calm to settle into. Kissena Park, a bit removed from denser commercial zones, provides shaded walking paths, a small pond, and lawns wide enough to sprawl out with a notebook. On the western edge of the borough, Socrates Sculpture Park — while technically a public art space — doubles as a reflective outdoor gallery and green space, with plenty of room to sit quietly among large-scale installations. If you’re closer to Long Island City or Astoria, Gantry Plaza State Park gives you space to look out across the East River and let the mental noise drop away.

Creativity in Queens isn’t always scheduled or advertised — it’s integrated into the spaces where people already live, speak, and share. And it’s best absorbed when paired with nearby quiet, when what you’ve made or witnessed can have time to settle. The borough doesn’t just let you create — it gives you space to reflect on why you did.

In The Bronx

In the Bronx, creativity often intersects with voice, movement, and presence. The borough’s history as a birthplace of hip-hop, street art, and spoken word shapes how artistic participation unfolds here: outward-facing, open to public space, and centered on expression that comes from the body. You’re not expected to sit quietly and watch — you’re invited to stand up and speak.

Open mic events and spoken word gatherings are a key creative outlet, held in parks, community centers, and occasionally in pop-up street venues, especially near Fordham or the Grand Concourse. These aren’t highly produced affairs — they’re free, improvised, and grounded in audience participation. Even when you’re not performing, being in the space is part of the creative act. Around Soundview and Hunts Point, mural painting and public art workshops offer another form of shared creation. Artists often invite passersby to contribute directly — with brushes, chalk, or hands — making the experience tactile and communal.

Once the expressive energy fades, the Bronx offers large, low-pressure places to let it land. Soundview Park, often home to the same events, opens up into a network of quiet paths and marsh-side benches. You don’t need to go anywhere to decompress — just walk ten minutes toward the water and sit in the reeds. Nearby, Concrete Plant Park offers a harder-edged but quieter landscape, with art installations and enough space to sit and write. If you’re further north, Pelham Bay Park gives you room to spread out, whether on grass or at the water’s edge, where the city feels farther away than it really is.

In the Bronx, creative work happens in public — not hidden in buildings but folded into the pace of a neighborhood. And because the city’s landscape opens up so generously here, the pause afterward feels earned. You speak, you move, you leave space — and the borough meets you with room to breathe.

In Staten Island

Creative expression on Staten Island often comes with an ecological undertone — a tie between art, environment, and place. This isn’t a borough known for its gallery circuit, but for its community centers, nature-based installations, and local art initiatives that operate at a slower, quieter rhythm. Here, creativity tends to emerge in parks, cultural outposts, and libraries — spaces shaped by routine rather than spectacle.

Several of Staten Island’s cultural hubs — including the Staten Island Greenbelt Nature Center and community branches of the NYPL — host small workshops in drawing, natural materials, and storytelling. These are low-key, sometimes seasonal offerings, but when they happen, they’re rooted in the land around them. Zine sessions, sketch circles, or painting meetups may unfold on picnic tables or under gazebos in local parks. There’s also a growing interest in creative wellness: mindfulness-based art, journaling in the woods, or silent sketch walks through the Greenbelt trails.

The best part is that these activities rarely require a shift to find stillness. The downtime is already there. Willowbrook Park, one of the Greenbelt’s more accessible nodes, offers wooded paths and a calm lake surrounded by open benches — a perfect place to reflect after a session or continue sketching in peace. If you’ve been working near the ferry or attending a program downtown, the waterfront promenade by the Staten Island Ferry terminal offers views, breezes, and space to breathe. Further south, the Conference House Park provides historic quiet and open coastal views where creativity feels less like an event and more like a state of mind.

On Staten Island, creative activity is threaded into the landscape. It doesn’t compete with the city’s noise — it responds to it by offering something slower. And when paired with nature that’s already in place, it becomes less of a detour and more of a rhythm you can slip into without needing to escape.

Cycling and Skating

In Manhattan

In Manhattan, the simplest way to cover distance — and experience scale — is to move on wheels. The borough is unusually well suited for cycling, skating, and rolling of all kinds, thanks largely to the Hudson River Greenway, which runs almost uninterrupted along the west side. It’s not just functional; it’s experiential. On a bike or skateboard, the island’s vertical architecture falls into rhythm with the horizontal stretch of water. Movement becomes fluid, continuous, and strangely quiet.

The Greenway is ideal for long, contemplative rides or short, playful bursts of speed. You can hop on near the Battery and ride all the way up past Harlem, with frequent entry and exit points along the way. For more structured terrain, the Pier 62 Skatepark in Chelsea offers one of the most expansive and thoughtfully designed skating spaces in the city, with bowls, rails, and flowing ramps — all beside the water. Farther downtown, Pier 25’s plaza-style skatepark caters to street skaters and beginners alike, with ledges, steps, and flat open areas for practice.

When you’re ready to ease out of motion, you don’t have to go far. Pier 45, located just south of the skateparks, offers a wide lawn with built-in benches and sweeping views — a perfect place to stretch out, cool down, or simply watch the water. Teardrop Park, tucked a bit farther inland near Battery Park City, is quieter and more secluded, with stone terraces and shaded seating that feel worlds away from the asphalt. And for those riding the Greenway further uptown, Riverside Park offers periodic stops with benches, flowerbeds, and overlooks where you can pause without leaving the river’s edge.

Rolling through Manhattan gives you a sense of how the borough moves — fast, linear, and energized — but it also reveals how accessible calm can be when you shift out of gear. With so many transitions built into the landscape, the ride and the rest become part of the same experience. You go until you don’t — and when you stop, the city keeps flowing around you.

In Brooklyn

In Brooklyn, wheeled movement tends to thread through neighborhoods rather than around them. Cycling and skating here are rarely about speed alone — they’re about connection, exploration, and the feeling of traveling a distance that would be invisible by train. Whether you’re biking the outer loops of Prospect Park or skating through open plazas in Downtown Brooklyn, the borough supports motion that feels improvisational and open-ended.

Prospect Park is the borough’s hub for both cycling and rollerblading, offering a full paved loop that’s closed to vehicles on most days and long enough to create momentum without interruption. For skaters, Golconda Skatepark in Downtown Brooklyn (also known as “Fat Kid Spot”) is a community-designed concrete space beneath the BQE — raw, informal, and packed with local character. Riders of all levels gather there, and the environment is built for repetition, progression, and presence. Around Red Hook and Sunset Park, waterfront bike paths are less crowded and offer long, meandering rides through industrial corridors and coastal wind.

Prospect Park has built-in transitions — just veer off the loop and onto the Long Meadow or into the wooded Ravine, where the hum of wheels fades and you’re surrounded by quiet. From Golconda, you’re only a short ride or walk to Brooklyn Bridge Park’s northern end, where seating lines the waterfront and open lawns stretch toward Dumbo. Red Hook, for all its distance from central Brooklyn, delivers some of the borough’s best slow moments — the waterfront paths and benches along Valentino Pier offer solitude, salt air, and low horizon lines that feel miles away from the density just inland.

Rolling through Brooklyn is rarely about getting from point A to point B. It’s about what you pass, where you pause, and how the borough’s shifting landscape invites you to slow down just as easily as it lets you build speed. The ride is the rhythm — and the rest is always built in.

In Queens

Queens rewards riders with space. While it doesn’t always offer the seamless bike infrastructure of Manhattan or Brooklyn, its expansive parks and open greenways make it one of the most satisfying boroughs for slower, longer rolls. Here, movement happens along the edge of the city — in wide meadows, under bridges, or on boardwalks where traffic fades and the skyline drops into the background.

Astoria Park is one of the most accessible launch points for wheel-based movement in the borough. With its riverside paths, generous open pavement, and clear sightlines, it supports everything from casual skating to focused laps on bikes. Nearby, the Roosevelt Island Bridge and connecting paths open up longer rides along the waterfront. Further east, Flushing Meadows–Corona Park offers paved loops and lakeside paths ideal for biking or rollerblading, with more room to maneuver than many Manhattan parks. While less well-known than Prospect or Central Park, these landscapes give riders a sense of openness that’s hard to replicate in denser neighborhoods.

Downtime is easy to build in. From Astoria Park, you can drift a few minutes north to Socrates Sculpture Park, which serves as both public art space and riverfront rest area — grass, seating, and sculptures spaced out for reflection. If you’ve been skating or riding near Flushing Meadows, head east toward Kissena Park, where tree-lined walking paths and a still, central pond create one of the quietest pauses in the borough. Gantry Plaza State Park, though slightly separated from the interior of Queens, offers a dramatic and calming finish to a riverfront ride, with wooden seating, skyline views, and enough space to sit still without interruption.

In Queens, wheels don’t just move you through space — they stretch your perception of it. There’s room to build up speed, and room to stop. The motion is often unhurried, the routes wide open, and the rest comes not at the end, but in moments layered between.

In The Bronx

The Bronx is a borough of long lines and sharp turns — built for riders who want their movement to feel connected to the land. Unlike the looped rhythm of Central Park or Prospect Park, the Bronx offers linear routes that trace rivers, hug bridges, and thread through neighborhoods with an edge of improvisation. Motion here follows the shape of the borough: direct, slightly raw, and full of transition.

The Bronx River Greenway is a standout route for bikers and skaters. This north-south spine stretches through a series of linked parks and riverside paths, allowing you to glide past marshes, gardens, rail yards, and restored wetlands — often with surprisingly little interruption. Sections near Concrete Plant Park and Starlight Park are especially open and flat, making them friendly to newer riders or those simply seeking a longer cruise. Skate culture also has a strong presence here, with community skateparks dotted throughout the borough — including spots near Soundview, Fordham, and the South Bronx Greenway.

Downtime is easy to access along the same routes. Concrete Plant Park offers shaded benches, public art, and an unobstructed view of the river — a space that feels quiet without being still. If you’re riding near Soundview, you can transition directly into Soundview Park, where open marshlands and broad fields stretch out toward the water. For a more immersive break, Pelham Bay Park offers a far wider expanse, including quiet coves, beaches, and shaded forest paths where wheels give way to walking.

Riding in the Bronx feels unfiltered. It’s not curated — it’s lived. The motion here isn’t only recreational, it’s part of how people navigate, commute, and decompress. And when you ride through it at your own pace, you get access to a version of the city that’s not packaged but real — with all the room you need to keep moving or slow down.

In Staten Island

Staten Island offers space to ride — more of it, and more quietly, than anywhere else in the city. With fewer crowds and longer stretches of uninterrupted road or path, wheel-based movement here feels like an escape, even when you’re still technically within city limits. This is where New Yorkers come to coast, to practice, or to just cover distance without dodging foot traffic or squeezing past cars.

The Staten Island Greenbelt provides unpaved trail routes for adventurous cyclists and smooth access roads for casual riders. It’s not designed as a bike loop, but the long, forested stretches and occasional parkways make it ideal for slower, scenic riding or exploratory loops on hybrid tires. Along the coast, the South Beach Boardwalk and adjacent promenades offer flat, ocean-facing pavement for bikes, scooters, and skaters — perfect for long glides with wide-open views. These coastal paths aren’t just pretty — they’re peaceful, with room to stretch out and keep your own rhythm without constant negotiation.

Downtime on Staten Island is often built into the ride itself. Willowbrook Park, located at the edge of the Greenbelt, is one of the easiest transitions from motion to rest — a large, wooded park with open fields and a quiet lake. If you’re riding near the eastern shore, the waterfront near Fort Wadsworth provides shaded picnic areas and elevated views of the harbor and the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. These aren’t crowded, programmed spaces — they’re open and reflective, designed for a pause that lasts as long as you need it to.

Rolling through Staten Island gives you a sense of what city motion feels like when it’s not defined by urgency. You can ride for the sake of the ride. You can coast without having to compete. And when you’re done, there’s always space to stop and let the motion carry on without you.

Water Views

In Manhattan

Manhattan’s relationship to the water is central to its identity — and for those who know where to look, the rivers offer more than just views. They become places of motion, restoration, and rhythm. Along the edges of the island, you’ll find activities that rely on the natural flow of the water, the openness of the sky, and the spaciousness that’s often missing just a few blocks inland.

One of the most unique and approachable ways to engage the river is through free kayaking. The Downtown Boathouse at Pier 26 offers short, guided paddling sessions during warmer months, with all equipment provided and no prior experience required. Nearby, Pier 96 also hosts free kayaking programs, operated by the Manhattan Community Boathouse. These experiences are low-pressure and communal, with volunteers guiding you into calm Hudson waters. Further south at Gansevoort Peninsula, you’ll find a newly designed riverfront space — Manhattan’s first public beach — with an athletic field and open sand ideal for barefoot movement, stretching, or casual games. It’s not a swimming destination, but it feels like a reset nonetheless.

After these kinetic experiences, the surrounding waterfront is rich with options for decompression. Teardrop Park, located just a short walk from Pier 26, is a compact urban refuge — its stone terraces and trickling water features provide coolness and quiet, even on hot days. For more open space, Pier 45 offers a generous lawn bordered by benches and soft light in the late afternoon. If you’ve ventured farther down the West Side, Battery Park provides not just gardens and harbor views, but also a broader emotional backdrop — ferries coming and going, the Statue of Liberty in the distance, and a feeling of pause at the edge of the city.

These waterfront rituals — paddling, playing, pausing — aren’t about spectacle. They’re about tuning into the scale and rhythm of the island. The rivers slow you down, whether you’re drifting just offshore or watching the tide roll in from a shaded bench. Manhattan may be framed by water, but it’s through these small rituals that the river becomes part of your day.

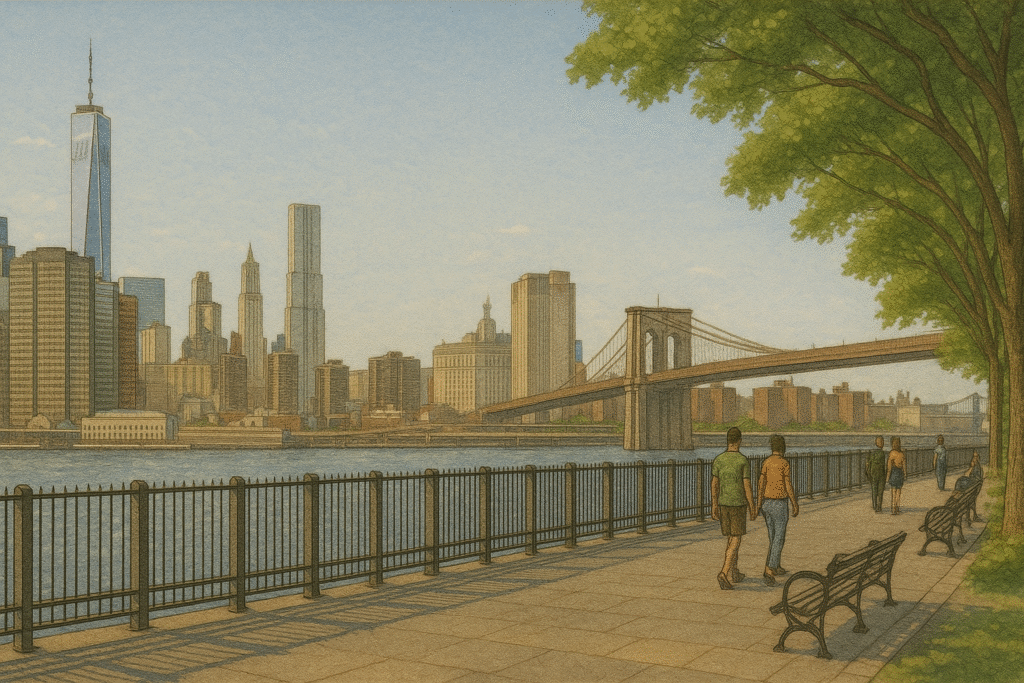

In Brooklyn

Brooklyn’s waterfront feels less like a single edge and more like a series of small frontiers. From the industrial quiet of Red Hook to the sculpted lawns of Brooklyn Bridge Park, the borough’s relationship with the water is varied and deeply local. Here, you can move beside the river without ceremony — walking, stretching, sitting, or watching — and each neighborhood’s shoreline carries its own texture and pace.

The piers at Brooklyn Bridge Park offer ample space for active use. Pick-up soccer, group yoga, and casual runs unfold against a backdrop of skyline views and ferry crossings. Farther south, the fields near the piers at Pier 5 and the edges of Pier 6 invite barefoot play, stretching, or calisthenics that feel more improvised than scheduled. Red Hook, quieter and less designed, hosts long, open sidewalks that wrap around the edge of the peninsula. Here, the movement tends to be solitary: joggers, roller skaters, or locals biking the wide, sun-bleached paths along Valentino Pier.

Downtime is as close as the bench beside you. In Brooklyn Bridge Park, the transitions are built in — move from turf to tree shade in seconds, or walk down to the rocks and sit at water level with just enough noise to feel buffered from the city. In Red Hook, the benches along the pier face west, which means you’re always oriented toward the setting sun. Sit with a snack, watch the ferries cut across the water, and feel the quiet settle in. If you’re closer to the southern end of the borough, the Narrows Botanical Garden in Bay Ridge offers river-adjacent walking paths and a surprisingly wild stretch of garden space where movement gives way to stillness, without crossing borough lines.

Brooklyn’s waterfront isn’t performative — it’s ambient. You can move through it without needing to perform a ritual, and yet the rituals form anyway. You stretch, you walk, you stop, you stare. And with the river at your side, each of those actions carries more space.

In Queens

Queens meets the water quietly. Its shoreline isn’t defined by landmarks or spectacle — it’s made up of long views, industrial edges, and unexpected softness. The waterfront here isn’t crowded with tourists or fully designed like in Manhattan or Brooklyn. Instead, it offers room to move without interruption, and places where a walk becomes a ritual simply because no one’s telling you where to go.

Gantry Plaza State Park in Long Island City is the most visible example — a clean, contemporary waterfront park with wide boardwalks, loungers, and bike paths that stretch along the East River. It’s often used for slow movement: long walks, light jogs, skate cruising, or just sitting beside someone while the skyline reflects back from across the water. In Astoria, the shoreline of Socrates Sculpture Park flows naturally into a walking path that skirts the river and opens up into neighborhood green space. Movement here feels casual, observational — punctuated by outdoor art, dog walkers, or the regular pace of neighbors finishing their evening loops.

When the movement ends, the pause is already close. At Gantry Plaza, you’re rarely more than ten feet from a bench, planter, or green patch that encourages you to stop. The sunsets are dramatic but not demanding — you can turn toward them or let them happen in your periphery. If you’re near Socrates, the slope of the grass itself invites sitting down. And a few blocks inland, Astoria Park provides a wider expanse of green with steady breezes and enough open space that you can lie back and disappear into your own pacing.

In Queens, the waterfront isn’t framed by spectacle — it’s wrapped in possibility. You move how you want to move, often without a crowd or camera in sight. You stop not because you’ve reached a destination, but because it’s easy to let your motion turn into rest. And when that happens, the borough gives you a place to stay still.

In The Bronx

The Bronx may not be the first place that comes to mind when you think about New York’s waterfront, but it’s home to some of the most spacious, underused, and quietly compelling river and bayfront access in the city. Here, the water feels close — not architecturally framed or fenced off, but part of the ground you’re walking on. Movement along the shore isn’t structured, but it’s intuitive. You follow the edge of the land, and the rhythm builds from there.

Soundview Park is one of the Bronx’s best examples of this. Situated along the East River, it offers a wide stretch of open fields, marshland paths, and bridges that give you constant proximity to the water. Whether you’re running, walking, biking, or just stepping out into the openness, there’s room to move and room to change direction. The South Bronx Greenway offers similar access: long stretches of sidewalk and riverside concrete that invite skating, rolling, or walking with nowhere in particular to be. Farther northeast, Pelham Bay Park borders the Long Island Sound and creates space for much longer loops — biking, hiking, or coasting — with sea air and wooded buffers that feel a world away from Midtown.

When you’re ready to pause, these same parks hold the calm. In Soundview, benches line the walkways facing tidal inlets, and even the more structured parts of the park feel like open invitation — sit, stay, do nothing for a while. Concrete Plant Park, farther inland along the Bronx River Greenway, offers a different kind of rest: angular, quiet, lightly urban, with enough space between benches that the silence feels intentional. Pelham Bay, especially the Orchard Beach area and the lesser-trafficked coastal trails, holds the kind of downtime you don’t have to share — shaded clearings, breezy bluff tops, and wide views over the Sound that never feel crowded.

The Bronx doesn’t insist on ceremony at the water’s edge. It lets you arrive as you are, move however you want, and stop when it feels right. And when you stop, you may find that the quiet has been waiting for you the whole time.

In Staten Island

Staten Island offers the most generous relationship to water in the city — not just because of its geography, but because of its scale. Here, the waterfront stretches long and open, with space to move without interruption and views that feel uninterrupted. There are fewer people, fewer fences, and more time. Whether you’re walking, riding, or simply standing at the edge, the water plays a steady role in the background of whatever you’re doing.

The South Beach Boardwalk is one of the most accessible and spacious places for movement. Long, flat, and often quiet, it supports everything from casual strolls to longboard gliding, group runs, or solo pacing. The breeze is constant, the view steady, and the rhythm self-determined. A bit farther inland, the Staten Island Greenbelt has several trails that run near creeks and marshy lakes — not quite coastal, but soaked in the same slow-moving water energy. Along the island’s west shore, occasional kayaking events provide a direct way into the water itself, organized through local boathouses and nature alliances.

For pause, Staten Island gives you options that feel undiscovered. Willowbrook Park, sitting just beyond the Greenbelt’s central zone, offers forest shade, a quiet lake, and open paths for slow walking or sitting beside the trees. If you’re closer to the water, Fort Wadsworth — perched on the edge of the Narrows — is one of the best places in the city to sit above the harbor and let the view carry you out. The ferry terminal promenade also provides easy, low-effort rest space, with built-in benches, harbor light, and wide river traffic unfolding in the distance. It’s not ornamental — it’s ordinary, which in this case is exactly the point.

Staten Island’s waterfront doesn’t require planning. You just show up, start moving, and stop when you’re ready. The space is there. The sound of the harbor carries. And for once, there’s nothing pressing in from behind.

Public Spaces

In Manhattan

In New York, even unprogrammed space can become the site of a performance, a gathering, or a spontaneous workout. Public space is not just where things happen — it’s where people create their own structure, together or alone. Manhattan’s parks and plazas, especially in its downtown and neighborhood cores, serve as informal playgrounds for both locals and visitors. These aren’t organized events, and they’re not necessarily athletic. They’re rhythms of use: spaces where people move, play, gather, and interact with the city on their own terms.

Union Square is a prime example. During peak hours, the park becomes a kind of civic stage — a chessboard, a drum circle, a breakdancing arena, or a quiet place to journal on the steps. Further west, the athletic fields and open lawns of Hudson River Park attract impromptu soccer games, frisbee, group workouts, or just families stretching out in the grass. Gansevoort Peninsula’s open sand, adjacent turf, and proximity to the water make it a new favorite for people looking to blend movement with lounging. These spaces are accessible without permission, often without plan — and that’s what makes them essential to the feel of the city.

When it’s time to downshift, you don’t need to go far. Jefferson Market Garden in the West Village is a short walk from Union Square, offering a gated patch of calm with flowering beds and benches beneath the gothic clocktower. DeLury Square Park in Lower Manhattan provides fountains, shade, and seating just blocks away from the noise of the Financial District. Sara D. Roosevelt Park, particularly its northern end, offers a quiet tree-lined stretch where you can watch neighborhood life without being in the middle of it. These small, often overlooked spaces give form to the city’s pause — a break from noise without leaving the neighborhood entirely.

In a city where public space is never truly empty, the playground isn’t always a literal one. It’s a mindset, a rhythm, a temporary community. Move how you want. Stay as long as you like. The city is already set up for it.

In Brooklyn

In Brooklyn, public space often feels like it belongs to someone — a block, a crew, a neighborhood. That doesn’t make it exclusive; it makes it lived-in. These aren’t stage-managed parks or polished plazas. They’re civic spaces in the truest sense: adaptable, open to interpretation, and shaped by how people use them day after day. Movement here doesn’t require structure — it builds its own.

Domino Park, perched on the Williamsburg waterfront, is a clear example of this layering. It has built-in play areas, turf fields, and spray zones — but its energy comes from the ways people use it: pickup games, acro yoga on the lawn, friends stretching before a run, parents holding informal toddler dance circles. In Fort Greene Park, the stone steps and central plaza function like a rotating community gym — early morning workouts, midday martial arts practice, or just someone trying new dance steps with headphones in. In Crown Heights, local parks like Brower and Lincoln Terrace see regular gatherings that look casual but unfold with daily consistency — tai chi, low-key bootcamps, jump rope, or small team sports that require no signup and no scoreboard.

The shift into rest often happens without a change of setting. Domino’s benches and hammocks are built into the same terrain as its playgrounds. You finish moving and fall directly into a slow rhythm. From Fort Greene Park, it’s a short walk to Fulton Street cafés or nearby pocket parks like South Oxford or Cuyler Gore — small but useful for decompression. In Crown Heights, even the shaded sidewalks become informal rest zones after activity, especially on blocks near Eastern Parkway or tucked-in gardens like the one hidden behind the Brooklyn Children’s Museum.

Brooklyn’s playgrounds aren’t necessarily designed — they’re performed into being. The permission to move, gather, or rest doesn’t come from signage or programming; it comes from precedent, presence, and repetition. You see others doing it, and you step in. And when you’re done, the city gives you the same freedom to stop.

In Queens

Queens has more languages spoken across its neighborhoods than any other borough — and in its public spaces, those languages become gestures, rhythms, habits. Parks here are less about design and more about function. They serve as extensions of homes, community centers, and sidewalks — places where movement is social, fluid, and shared without announcement.

Travers Park in Jackson Heights is one of the clearest examples. It serves as a meeting place, a play space, and a stage — all at once. In the early hours, it hosts seniors doing tai chi. Later in the day, kids run games that shift shape by the minute, while teens practice choreography or music under open-air pavilions. In Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, the lawns and lakeside paths offer more formal space, but the feeling is the same: cricket on the grass, group fitness beside the water, and impromptu dance circles near the playgrounds. The park is expansive, but it’s used intimately — defined more by neighborhood ritual than by planning.

The transition to rest happens in-place or just around the corner. From Travers Park, it’s only a short walk to a quieter stretch of sidewalk or a neighborhood bakery bench. If you’re in Flushing Meadows, you can drift toward Kissena Park, where the noise drops away and the pond, shaded trails, and grass invite reflection instead of repetition. Socrates Sculpture Park, on the western edge of the borough, blends both motion and rest: you might move through it in slow observation, then sit on a slope beside the water, watching as people do the same.

Public space in Queens is rarely empty — but it’s rarely overwhelming. It holds multitudes in motion. You can join a game without asking. You can watch from the edges without explanation. And when the motion ends, the quiet doesn’t feel like withdrawal — it feels like part of the same performance.

In The Bronx

In the Bronx, public space is a canvas — sometimes literal, often improvised, always alive. Movement here is expressive and unstructured, shaped by rhythm and history as much as terrain. The borough’s parks are not passive green zones; they are stages, courts, gyms, and living rooms, where what counts as activity is broad and flexible. You don’t need a field permit or a posted schedule — you just need a body and a reason to show up.

St. Mary’s Park and Claremont Park are strongholds of this energy. On any given day, you’ll see fitness instructors leading group workouts beside informal martial arts drills, or watch breakdancers warm up on concrete while kids cut through basketball courts with scooters. The movement in these parks isn’t assigned a lane — it flows and overlaps, sometimes colliding, often harmonizing. In Soundview Park, the open fields and riverwalks give space for movement that stretches out — kite flying, freeform jogging, or simply walking in wide arcs through grass and gravel.

When the energy dips, the pause is close by. Soundview Park itself holds the silence — its wetlands and side paths absorb sound, and benches along the water face low tide and open sky. For a sharper change of pace, Concrete Plant Park offers a more sculpted kind of stillness — with art installations, river views, and a harder aesthetic that doesn’t ask you to relax, but gives you space if you do. North of the denser neighborhoods, Pelham Bay Park opens up into a landscape that feels rural by comparison: wooded trails, beachfront walks, and long clearings where movement gives way to openness.

In the Bronx, the line between play and performance is thin. The public spaces aren’t just backdrops — they’re part of the action. You arrive, you move, and you watch others doing the same. And when you step out of it, the city doesn’t stop — it just keeps playing without you, until you’re ready to step back in.

In Staten Island

In Staten Island, public space operates on a different rhythm — less compressed, more spacious, and shaped by how people gather in proximity to landscape. The borough’s playgrounds aren’t always built — they emerge where paved trails meet picnic tables, or where a shaded lawn invites movement without a plan. Because Staten Island isn’t organized around crowd density, public spaces here invite slower, more fluid interpretations of activity — from family walks and quiet soccer matches to sketching under a tree or simply stretching with the tide.

Willowbrook Park offers one of the clearest examples of this fluidity. It includes playgrounds and structured sports areas, but its center is much more open-ended: trails, soft hills, a lake, and long sightlines that support self-guided movement. You’ll see families setting up ad hoc badminton games, teens riding in wide figure-eights, and solo visitors circling the pond in rhythmic laps. Farther south, the open coastal zones near Conference House Park serve as unintentional stages for loose movement: group strolls, nature walks, or even slow bike drifting along wooded paths and sandy shorelines.

Downtime is rarely separate from the motion. In Willowbrook, the lake’s edge and surrounding benches create natural transitions into rest — nothing separates the play from the pause. Near Fort Wadsworth or along the South Shore, picnic areas, dune-facing benches, and seawalls offer equally easy options for sitting still. Even the ferry terminal’s promenade, despite its functional surroundings, gives enough open air and harbor view to feel like a place to settle without needing a plan.

Staten Island doesn’t rush its public space. It lets you arrive without agenda, move as long as you feel like moving, and settle as quietly as you want. Here, the playground isn’t just a feature — it’s a mood, one shaped by land, water, and a shared understanding that not everything has to be fast to be alive.

How to Build a Day

A good day in New York doesn’t follow a checklist. Even the most flexible days benefit from some structure. That means acknowledging the pace of the city: how long it takes to move through it, how time can evaporate between subway stops, and how meals and crowds shape your energy whether you plan for them or not. Building a satisfying day here isn’t about doing everything — it’s about doing fewer things with greater attention, and knowing how to shift between motion and stillness without burning out.

Start by choosing one or two main activities — something active, communal, or creatively engaging. These could be located in the same borough or span across two, but it’s important to account for time. Even a 45-minute kayaking session or outdoor workshop can easily expand into two hours once you include transit, orientation, conversation, and wind-down. Choose your core moment, then place downtime directly before or after it — a park nearby, a waterfront bench, a plaza with seating. This isn’t filler; it’s part of the day’s pacing.

Think in arcs, not timelines. If your main activity is in Manhattan’s West Side (say, skateboarding at Pier 62), your slowdown might be Teardrop Park or Pier 45 — both within walking distance. If you’re planning a ceramics workshop in Gowanus, you might wind down in Prospect Park or a quiet green patch near the canal. The point isn’t to “cool down” in a formal sense, but to design your movement with contrast: active → still, loud → quiet, public → private.

Consider sticking to one borough if you’re walking and taking it slow. A single-borough rhythm might mean: tai chi at Travers Park → zine workshop nearby → sunset at Gantry Plaza. If you’re up for covering more ground, pair neighborhoods with direct transit or ferry routes: kayaking on Staten Island → ferry to downtown Manhattan → reading at Greenacre Park → improv class near Union Square. These cross-borough rhythms take longer but offer a broader feel of the city — especially when planned around travel windows that avoid rush hour or long transfers.

Timing matters too. If you’re hungry between 11:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. in Midtown, expect lines, delays, and noise. Instead, eat early or late — and build the rest of your day around those flows. Avoid switching subway lines during weekday rush hours, and use ferries as both scenic shortcuts and recovery time. The Staten Island Ferry, in particular, is one of the best midday transitions you can take — built-in views, a breeze, and twenty-five minutes of seated calm with no pressure to perform.

Most importantly, don’t overprogram. The rhythm isn’t about squeezing in more — it’s about tuning your awareness to the city’s shifts in volume, density, and pace. When you allow space between activities, that’s when the spontaneous things happen — the overheard conversation, the side-street you hadn’t planned to turn down, the quiet corner of a park that you suddenly need more than anything else. Those are the parts you’ll remember.

You don’t need to follow anyone’s itinerary. You just need to know how to build a day that feels like yours.

At this point, you’ve seen how New York’s five boroughs offer a spectrum of movement and stillness — from free fitness classes and creative workshops to skateparks, ferry rides, and quiet lawns tucked between buildings. What makes a good day here isn’t how much you cover, but how well you balance your energy across space and time. This final section helps you pull from the categories and places you’ve seen and turn them into a shape of your own.

Begin by picking a main experience. That could be a physical activity (like kayaking in Queens or skating in the Bronx), a creative moment (such as a ceramics drop-in in Brooklyn), or a spontaneous neighborhood gathering (maybe tai chi in Travers Park or an open mic in the South Bronx). Treat this as your day’s anchor.

Then find a nearby downtime spot. Use the pairings throughout this guide — a park within walking distance, a waterfront bench, a shaded plaza — where you can linger without needing a plan. The idea isn’t to rest for the sake of recovery, but to let the experience settle. This is where rhythm replaces itinerary: one action flows into quiet, which makes space for what comes next.

From there, you can layer in a second arc — another movement experience or another pause — depending on your time, curiosity, and mood. Maybe it’s a ferry ride to a different borough, or a walk through a sculpture park at sunset. Maybe it’s a spontaneous game, or a meal that turns into an hour of people-watching. Leave room for improvisation, but ground your day in contrast: effort followed by softness, noise followed by space.

New York moves constantly. It’s also full of small pauses and quiet views. Build your day with those in mind.

New York isn’t something to conquer — it’s something to move with. You can sprint through it and see a lot, or you can do it like a New Yorker.

Whether you’re here for a day or a season, this guide isn’t about doing everything. It’s about doing what makes your experience real — a few hours in a park you’ve never visited, a free class with strangers, a sunset by the water in the evening. That’s the version of New York you’ll carry home with you.

The Street Sign

The Street Sign points the way to where things are — the parks, restaurants, museums, and everything else. These guides are built to save you time and energy. Need a plan for an NYC outing? Follow The Street Sign.