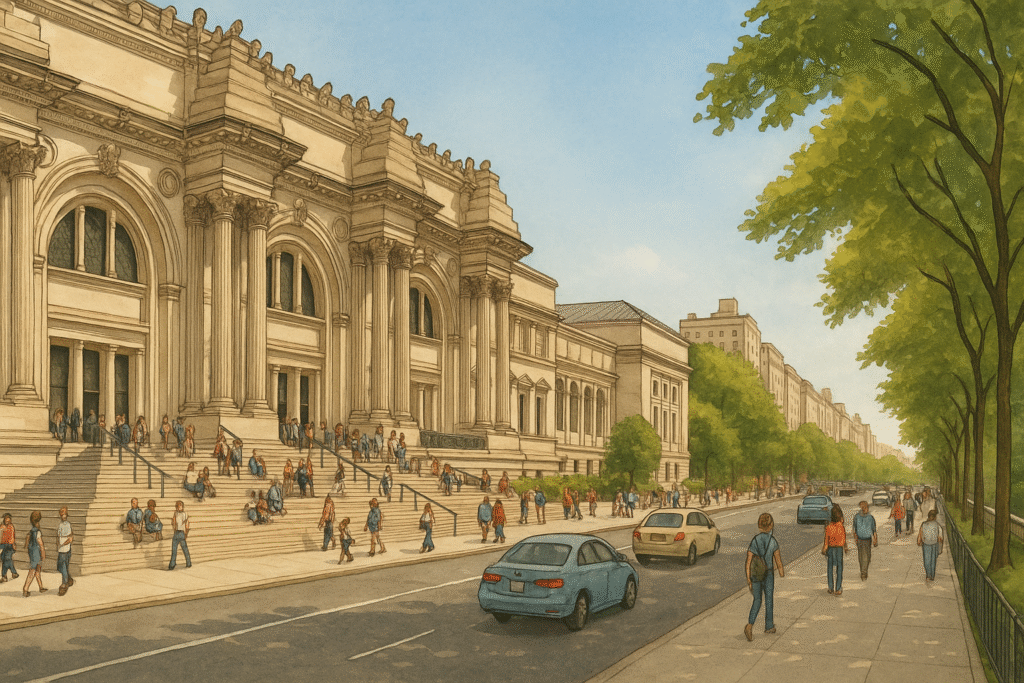

The Metropolitan Museum of Art rises from the edge of Central Park with a scale that suggests not just a museum, but a world unto itself. Its facade stretches across Fifth Avenue, where a broad stone staircase leads to the columned entryway. Visitors pass through a set of towering glass doors into the Great Hall, a vast rotunda where vaulted ceilings echo with footsteps and gallery maps rustle in hand.

The Met spans more than two million square feet, and its layout unfolds in layers. The central information desk stands just beyond the entrance, surrounded by arches that lead in every direction. Galleries branch off in chronological and geographic sequences, forming a kind of time-travel circuit that spans millennia. First-time visitors can orient themselves by picking up a floor plan and asking a guide stationed near the front for current gallery closures or detours.

There is no single way to navigate the museum, but certain routes offer a coherent and rewarding flow. The Egyptian wing lies directly behind the Great Hall, while the American Wing extends off to the right. A staircase near the Arms and Armor Court leads to the European Painting galleries above. Elevators and ramps are available throughout, and museum benches are placed at regular intervals for rest and reflection.

The museum recommends reserving timed entry in advance, although same-day tickets are available at the counter. Bags must be checked or worn on the front, and visitors are encouraged to travel light. For longer visits, there are several on-site dining options: a ground-floor cafeteria, a casual café in the American Wing, and seasonal rooftop service when weather allows.

This day’s visit moves deliberately through the museum’s most iconic spaces, balancing ancient artifacts with fine art, architecture, and open air. The journey begins at ground level, where sunlight filters through a glass enclosure framing one of the Met’s most dramatic sights.

Foundations and Antiquities

From the Great Hall, the galleries behind the information desk lead directly into the museum’s ancient past. The first space opens into the Egyptian Art wing, where a long, vaulted corridor guides visitors toward one of the Met’s most iconic installations: the Temple of Dendur. This sandstone structure stands in a soaring glass enclosure, surrounded by reflecting pools and framed by views of Central Park. Originally built by the Roman governor of Egypt around 15 BCE and gifted to the United States in 1965, the temple remains intact, weathered, and visibly marked by centuries of inscriptions. Visitors can walk around its perimeter, view ancient graffiti carved into its columns, and step inside the structure itself.

The surrounding galleries house intricately painted coffins, bronze animal figures, and reliefs carved with hieroglyphics. Most of the objects are displayed in low glass cases, making the space navigable for visitors of all ages. Natural light enters from above, and seating is available along the walls and near the temple platform.

Continuing past this gallery leads to the Greek and Roman collection, where the museum’s marble floors echo underfoot. These rooms present large-scale sculptures, including freestanding Roman copies of Greek originals, mosaics once set into palace floors, and bronze armor arranged on upright mounts. Many of the pieces are placed in open view, allowing visitors to walk around each object fully. The galleries alternate between whitewashed spaces and warm-toned walls, creating a rhythm that helps distinguish regional and chronological transitions.

Just beyond this wing, a hallway opens into the American Wing, where a skylit courtyard houses 19th-century sculptures, decorative urns, and architectural fragments. This space, known as the Charles Engelhard Court, includes the façade of a New York bank salvaged and reconstructed inside the museum. Visitors can rest at benches near the reflecting pool or move through surrounding rooms filled with colonial-era furniture, stained glass, and Hudson River School landscapes.

This early portion of the route introduces the museum’s breadth and visual diversity. From ancient stone to neoclassical sculpture, each space is arranged with a sense of scale and flow, designed to support lingering or continuous movement. Paths are wide, transitions are seamless, and entry points to new rooms remain visible from across the floor.

Masterworks and Material Cultures

From the American Wing, visitors can move up a grand staircase or take the nearby elevator to the second floor, where the European Paintings galleries begin. These rooms display some of the most recognized works in the museum’s collection. The sequence opens with Dutch and Flemish masters, including luminous canvases by Vermeer, moody portraits by Rembrandt, and intricate still lifes that fill narrow vertical walls with texture and shadow.

The galleries are arranged by school and period, with clearly marked transitions. Just beyond the Dutch wing, the path shifts to French Impressionism, where wide doorways reveal brighter spaces lined with works by Monet, Degas, and Renoir. Paintings are spaced to allow for unhurried viewing, and benches are placed in the center of each room. Further along, the turn of the 20th century appears in vivid brushwork and altered scale, with canvases by Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin marking the edge of tradition and the start of modern abstraction.

From here, the route curves toward material history in the Arms and Armor galleries on the floor below. This series of vaulted halls features mounted knights, full suits of plate armor, and ceremonial weapons arranged by region and purpose. The main entrance opens onto a dramatic display of horses and riders in formation, ringed by glass cases holding swords, helmets, and shields from Europe, Japan, and the Middle East.

Adjacent to this area, the Medieval Art galleries house reliquaries, tapestries, and carved altarpieces arranged under vaulted ceilings and low lighting. Stone sculptures from Romanesque churches are mounted at eye level, while stained glass windows frame the space with color and narrative detail.

Visitors with more time can explore adjacent wings, including the Art of the Islamic World, which presents ceramics, textiles, and calligraphy across a long, luminous corridor. The rooms feature intricately tiled walls and low display tables, offering a slowed rhythm and clear sightlines.

This middle portion of the visit highlights the Met’s ability to hold fine art and cultural artifact in balance. From portraiture to armor, and from oil on canvas to gilded wood, each gallery offers a view not only of beauty, but of the hands and histories behind it.

Open Space and Evening Options

After hours inside the galleries, visitors can step into the open air by taking the elevator near the European Sculpture Court to the museum’s Roof Garden. This seasonal terrace opens in the spring and closes in late fall, weather permitting. At the top, a wide platform overlooks Central Park and the Manhattan skyline. Sculptural installations rotate each year, often created specifically for the space. The terrace includes a small bar, shaded tables, and a long railing facing the treetops.

Back inside, evenings at the Met take on a quieter tone. On Friday and Saturday, the museum remains open until 9 p.m., and the Great Hall Balcony Bar becomes a calm space to rest before departure. Located above the main entrance, this mezzanine lounge overlooks the lobby’s arches and columns. Guests can order wine, cocktails, and light appetizers while seated beneath vaulted ceilings and chandeliers.

Before exiting, visitors often stop at one of the museum’s gift shops, which are located on multiple floors. The largest sits near the main lobby and offers a wide selection of exhibition catalogs, art books, prints, and design objects. Smaller shops throughout the building feature focused collections tied to specific galleries.

The final route passes again through the Great Hall, where ticket desks grow quiet in the late afternoon and footsteps echo in smaller groups. Visitors exit either down the central staircase to Fifth Avenue or through side ramps for accessibility.

A full day at the Met offers more than a checklist of galleries. Each space presents a setting shaped by light, texture, and arrangement, allowing visitors to move through collections in ways that feel intuitive and unforced. Seating is present throughout, and transitions are marked by open thresholds rather than barriers, which helps maintain momentum even during longer visits.

Whether entering through the Grand Hall or stepping onto the rooftop, the museum provides moments of perspective—both visual and physical. Visitors can pause beside a sarcophagus, a window, or a Vermeer, and take in what surrounds them without needing to rush.

The Met supports exploration at many levels. It is structured enough to guide, yet flexible enough to invite improvisation. A half-day visit may follow a linear path. A full day may circle back, doubling through galleries with new eyes. The architecture accommodates this kind of movement.

As the doors open once more onto Fifth Avenue, the city resumes its rhythm. The museum remains behind, not as a single memory, but as a sequence of rooms walked, seen, and felt. The route concludes where it began—with an entryway, a decision, and the time to follow it.

The Street Sign

The Street Sign points the way to where things are — the parks, restaurants, museums, and everything else. These guides are built to save you time and energy. Need a plan for an NYC outing? Follow The Street Sign.